Nouns of Logooli

There are many nouns in Lulogooli. Table Ileseni 18a and 18b lists some of them.

More on Vilaange (nouns) is that they can be grouped into several groups due to their characteristics. This grouping only helps us understand more about them and even be in a position to study them.

The Vilaange groups are; Vigulika(proper nouns), via Kase(common nouns), Vivalizwa(countable nouns), Vitavalizwa(uncountable nouns), via Masaanga (collective nouns), Viveeho (Concrete nouns), Viganaganwa (abstract nouns) and Vinavikolwa (gerunds/nouns from verbs).

The above are highlighted in chart Ileseni 18c with examples.

A brief look at each of them is that Vigulika(proper nouns) are names that officially recognizes a specific place, a person or thing. The names does start with a capital letter as “Ivulogooli” and “Mwenesi”.

“Kugulika” is to give a name. Often a name is given under various reasons to serve several Logooli meanings. Some names are; “Onzere”(person). Nairobi(city), Maragoli TV(company), Mulogooli, Mukilima(clan).

More on people and about Vilaange via kugulika (people’s nouns) are expounded in table Ileseni 18e.

Vilaange via Kase(common nouns) are used to name people, places or things but in general. They can also be called family nouns and are always (kase) implied.

Vilaange via kase include; maama(mother), kiitu(market), ing’oombe(cow), mudoga(car) and others.

There are countable(vivalizwa) and uncountable(vitavalizwa) nouns. The countable ones have plurals as provided in the noun class table Lesson 11 of Ululogooli.

The countable nouns include; kikoombe-vikoombe(cup-cups), muana-vaana(child-children), liinu-mainu(tooth-teeth), lubaanga-zibaanga(matchette-matchettes) and others.

The uncountable ones include; mazi(water), vusela(porridge), masaahi(blood) and others.

Collective nouns in Lulogooli are known as Vilaange via masaanga. They refer to a set of people or things. And they are always followed by a plural word.

Examples of collective nouns are; iluku ia valwaani(gang of fighters), kiayo kia zing’oombe(herd of cattle), kiduma kia zingoko(flock of hens) and others.

Next are concrete and abstract nouns. They are in Lulogooli known as Vilaange viveeho (that are in existence) and vilaange viganaganwa (that are perceived to be) respectively.

Vilaange viveeho include; imbwa(dog), isiimu(phone), mulimi(farm), musaala(tree) and others. Vilaange Viganaganwa examples are: vuyaanzi(happiness), vulogi(sorcery), malooto (dreams) and others.

There are nouns that take two or more words to be created. These are known as Vilaange vigelekana in Lulogooli. They are equivalent of “compound nouns” in English.

“Kugeleka” is to add something on top of another. Examples nouns are: Kigwi-ndole(care free), kazya-nda(meat), ituliza-mate(foam insect), chinyala-moni(eye urinating insect).

When nouns are derived from verbs, Ululogooli uses them to refer to a person, place, activity or things. These are known as Vilaange-vikola (noun verbs). In English they are the gerunds.

Example gerunds in Lulogooli are; linyangula(running), kusava(begging), ilya(food), inganagani(thought) among others.

Picture chart of Ileseni 18d above illustrates some of the described nouns.

Exercise

- Write the Lulogooli and English equivalent of noun groups and their characteristics

- Identify two more nouns for each group of nouns

...

Family and Relatives Common Nouns

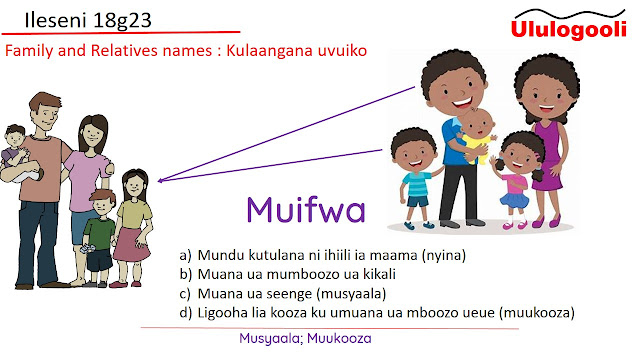

The names given to family members and relatives are common nouns. The names are mainly to express kinship relations.

Each family member applies the names and it can be how you refer to someone or how they refer to you.

Lulogooli society is set up in an extended family model and the web of names are to be particular with which person are you referring to.

The names include; “maama, baaba, seenge, museenge, guuga, guuku, amwaavo, amiitu, mboozo, kooza, mukooza, muifwa, musyaala, mulamwa, muhalikwa, navizala, vasaangi, muana, muisukulu, kiisukulu, kiisukuluulwi, kisoni, kizyenye, kifudulamoni, muikula, muguuga, muguuku, umumaagu, umaama, muko, mukwaasi, vasegwa, musaaza, mukali, musigu,”

The above names are illustrated in the charts Ileseni 18g1 to Ileseni 18g25 as below.

It is also in the context of family names that Ululogooli gets particular with gender. One is considered either male or female.

A name as “Mboozwa” refers to a brother or a sister, only of opposite sex. When you are of same sex it is “amwaavo”.

Whereas the brother to your father is still your father, “baaba”, the brother to your mother is “kooza”. Though both masculine names, traditions uphold paternal descent greatly.

The difference between one or the other “baaba” is by adding their age in form of elder or younger. If you are referring to elder brother of your father, it is “baaba munene”. The younger is “baaba muke”.

Same to giving respect is when father in law is known as “muguuga” from “guuga”, grandfather. This is to show great reverence and increase mutual respect between the in-laws.

A name as “Seenge” is neutral in application but associated with “aunt”, female. “Seenge” is the sister to your father. The sister to your mother is still your mother.

But the brother to your mother is “Kooza”, a very respectable name in Ululogooli. He calls his sister’s children, “vakooza”, denoting “of his blood – though maternal”.

The husband to “seenge” is still “seenge” but one can add, “seenge ua kisaaza”(male aunt). When aunt is referring to you (you as the child of her brother), the salute is “museenge”.

The children of “seenge” are “vasyaala”, one is “musyaala”. They are also called “vaifwa”, a denote of having you maternal blood.

A husband of is “musaaza ua”. My husband is “musaaza uange”. A wife is “mukali” although a gracious name is “mudeeki”(cook).

A wife to your brother is outwardly “mulamwa” but inwardly “mukali” due to the oneness of paternal family. “Mulamwa” is also the salutation from husband brother to brother’s wife or brother’s wife to brother’s sister.

“Muhalikwa” is a name that same age group women call each other in a family. These women could be the wives of same person or wives of brothers.

The highest hierarchy name is “guuga”(grandfather) and “guuku”(grandmother). From there is a series of generations downwards, permanent in paternal hierarchy.

The generations are; guuga(grandfather), baaba(father), muana(child), muisukulu(grandchild), kiisukulu(great grandchild), kiisukuluulwi(great great grandchild), kisoni(great great great grandchild), kizyeenzye(great great great great grandchild) and kifudulamoni(great great great great great grandchild).

Early ancestor before the above can be called according to what grandfather is called in the geneations. For example, “who calls my grandfather great grandchild” is ancestor number 9 before you.

Down the hierarchy, one maintains the paternal identity. This is cemented by a clan or tribe name. For the maternal generation, the third generation is free to disassociate from earlier made relationships and can intermarry – yet not in the very matriarch’s bloodline.

Exercise

- Study the chart Ileseni 18f and draw your family tree

- Using the illustration of Ileseni 18g1-18g25, expand the name table so that everyone in the hierarchy calls and is called.

...

Age-sets

Other nouns in Lulogooli are the age-sets. They can be said to be proper nouns as they are specific with age-groups. The documented ones are 39 in number as in Ileseni 18h below.

The Age-sets provide time and historical context from which comprehensions for Lulogooli can be developed. Each age-set varies from another by a period of averagely 7-10years.

Whereas the earlier age-sets may not be clear with ages, perhaps the recall can help historians work on approximates, as they are akin to Kalenjin names of age-sets.

As to date, the a few oldest are of the Lizuliza (1938) age-set while the youngest are Lumuli (2023) age-set.

The age-set name is for both boys and girls. Logooli does not circumcise girls but to commemorate age-set, girls would be scratched on the skins to adopt the given name.

Circumcision for boys remains an important Logooli rite as it brings together the community and instils cultural sense among all who participates.

Exercise

- From your family tree in Ileseni 18f, identify each person with their age-set name

- Describe the events during your own initiation or age-set happenings

...

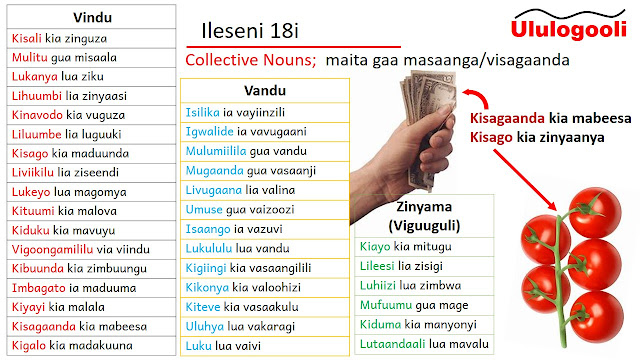

Collective nouns

Collective nouns of Lulogooli are words that refer to a group of people, animals or things.

For example, a bunch of vegetables is called “kisali” while a herd of cows is “kiayo”.

From the words “Kisali” and “Kiayo”, the group words are singular. It can only be plural if the mentioned nouns are in groups of separate identities.

For example, “kisali” is one bunch while “visali” are two or more bunches. “Luku” is a gang of people. If we have two or more gangs, they are “ziku”.

A group of noun when followed by the people or things name, the described persons or things are written in plural. Examples are “kiayo kia zing’oombe” (herd of cows), Mulitu gua misaala (forest of trees), Mufuumu gua mage (army of ants)” and more.

Sometimes two or more collective nouns can be used to refer to the same thing. A “bunch” can be “kisagaanda, kisali or kisago”. Table Ileseni 18i lists several of the collective nouns.

The characteristic of the nouns in addition to style and attitude of the speaker influence meaning in Lulogooli. If a bunch of flowers is called “kisali” for instance, it were as well compared to vegetables. Or is a group of demnostraters is called “kiayo”, it were as well compared to cows (timid or mild people).

Exercise

- Read aloud collective nouns as in table Ileseni 18i

- Ask about any other collective nouns in Lulogooli to add.

...

Compass Directions

Compass directions also add to the collection of Logooli nouns. The Directions are important in showing the side - near or away.

A side or direction in Lulogooli is “luvega”. By saying “Luvega lua” it means “the side of”. Asking “Luvega luliha?” is “what side?”

The Four main directions for Lulogooli are “Ivaale, Ivugwi, Isavaalu & Imadyooli” for North, East, South and West respectively as in chart Ileseni 18ka.

The directions are all prefixed “I-” from noun class 9{i} where locatives of Lulogooli are. When you say “Imutwi” is “by the head side”, “Inyuma” is by the back side” and forth. Though uncountable, when severally implied, the plural apply; “zivaale, zivugwi, zisavaalu & zimadyooli”.

Standing while facing Ivugwi, the back faces Imadyooli while the left and right hands point to Ivaale and Isavaalu respectively.

Other Traditional names for these compass directions are commemorated in several ways. Ivugwi is identified with new land and goodness, “uvugwi”.

Imadyooli is identified with gloom, setting. It is “I-ua-Madwaasi”. A story is told about a man known as Madwaasi who mourned for his mother bitterly when she died (I-ua-Madwaasi aaikuulila nnya). It was in the West.

Isavaalu is lake-side, where traditionally, trade used to happen a lot. And also borrowing, “kusava”. The common market, “Jivaaswa” presently at Kiboswa is synonym to Isavaalu, “Ijivaaswa”.

Ivaale, the North, reminded Valogooli of origins. Traditional burials had the diseased face North, where “Valogooli came from”. The North signifies Misri, land of ancestors. Recently, North became “Kieywe <Chyeywe>”, present Kakamega town.

When a direction is between the mentioned four above, Ivaale and Isavaalu start before saying if Ivugwi or Imadyooli to it. A direction as North-East is Ivaale lua Imadyooli as in chart Ileseni 18kb.

Exercise

- Stand facing Ivaale and draw yourself in your notebook identifying directions surrounding you.

- Identify places located in the various directions from where you are/stay.

...

Time in Lulogooli

Reading and saying time as part of writing is added to the nouns. The names of hours, minutes, seconds and what else names time of the day is important to grasp.

The traditional reading of time is through repeated events. This includes the rising and positioning of the sun in the day and density of darkness or silence in the night.

Activities of the day would tell what time it is as illustrated in Chart Ileseni 18ld. Normally, waking up is “Mulivuuka”, rising of the sun is “Mulitoonga”, going to various activities is “Mulisamula” and forth.

The traditional time has changed and modern times have taken shape. An event as “Muliteela” (roosting) that happened before midday is now not common as many people do not keep hens and those who keep for industrial purposes have the hens lay day and night.

Another disrupted time is “Muligelela”. This was moments before dusk when cows would be brought back from grazing for milking and locking in shades. It was different from “Liinuka” which meant “leaving work”. Farm work only stopped a few moments after mid-sun. Yet today both “Liinuka & Muligelela” happens late in the day as people come home from work.

The Watch is now a common tool for time reading. In Lulogooli, the watch is “Isa”. Perhaps its figurative sense is the Logooli loud insect, “Isa”, Giant Forest Cicadas. The insect from which the name is borrowed is known for its timely noisy shrill while holding on a tree. It is very loud and can be heard a far. It is said that males are the ones responsible for the sound, producing sound using specialized tymbals and their hollow abdomens as resonators.

The man-made “isa” is set with numericals (ziduguta) for reading time. In Lulogooli however, time is read in Bantu format. The first hour is at dawn, isa ilala (<sa-mooja>). The rest of the hours follow in a numerical format.

The top of the watch faces number 6, “isa ia siita (<sa-siita>)”. That goes with positioning of the sun in the sky or underneath at night as in Chart Ileseni 18la.

People often cut short time “(<sa-siita>)(time six)” from “isa ia siita” (the time of six). It is important to write in full in answering the question, “Ni isa ia ki?”, what is the time of? And as it would be saba7, munaane8 or forth, traditionally it would be “Isa ia kudeeka”(time to cook) or “isa ia zidaaywa”(cockcrow).

At o’clock is “Kuimbala”. This is also “on the mark”. Kuimbala, all the three hands of a watch rest at the same place, hour hand (mukono gua isa), minutes hand (mukono gua zidaakika) and seconds hand (mukono gua zisekondi) as illustrated in chart Ileseni 18l.

A minute past is “Iakavita idaakika”. When a few minutes pass, it is “Ziakavita zidaakika”. To pass is “Kuvita”. Often, an hour is added minutes in the formant, “Ni isa ia saba na zidaakika munaane”, it is seven o’clock and eight minutes.

A quarter, half and three quarter past is known as “ilobo, inuusu & zilobo zivaga” respectively. An hour and passed time is given as in examples, “isa ia kane na ilobo”(04.15). The English equivalent is *10.15*.

Time remaining is said to be “ikile” in singular and “zikile” in plural as in Chart Ileseni 18lb. Two hours to time is “zikile zisa zivili”. If it is about minutes, one can give an example, “Zikile zidaakika saba iduuke isa ia likomi muvudiku” (Remainder seven minutes it clocks four in the night).

Words “mumuvasu/muvudiku” are added at the tell of time to denote if day or night respectively. An example sentence is, “Iali isa ia likomi na ilala mulidiku lua aaduuka”(It was at 5.00pm when she arrived). Muvasu/lidiku represents before-meridian(am) while Hamugoloova/vudiku is post-meridian(pm) as in chart Ileseni 18lc.

A day (ilidiku) is divided into two, mumuvasu and mukisuundi (sunny and dusk). Sometimes the word “lidiku” denotes morning before late evening. The morning hours of the day before noon (vuila) is known as “mugaamba”, while the remainder time to dusk is “hamugoloova”.

The night is divided into “vudiku” (before midnight(vudiku vunene)) and vuchyezaa (dawning). Other words that describe dawning are “muzidaaywa”(in cockcrow), mumavweevwe(early morning), mumanyonyi(in birds).

Exercise

1. Draw an analogue watch at your notebook and name the components in Ululogooli.

2. Mark your daily routine in hours and note at the hours in your note-book

...

Days and Seasons

Having outlined times of the day in Ileseni 18l, next is to look at what several days make and also events in it.

One day is “lidiku lilala” while two days is “madiku gavili”. This follows the numbers, with week having “madiku saba”, a month averaging at “madiku salasiini”.

A few days past in Lulogooli is listed as, “mugoloova” for yesterday, “mugoloova-guavee” for the day before yesterday, “lua-igolo” for three days before today. Time that will be is added with "-liva". Tomorrow that will be, indefinite, is "mugaamba guliva" while past is "mugoloova guali". This is outlined in chart Ileseni 18ma.

Days to come are, “mugaamba” for tomorrow, “mugaamba-guizaa” for tomorrow but one and “mugaamba-niguve” for third day from today.

The Logooli days of the week started by highlighting the week, “Mulisiiza”. This is today Sunday, also taken as a rest day, “Lihoonga”. This was due to the activities the day before, “Liengeesa” for gathering/harvesting. Today it is Saturday and written “Muliengeesa”.

A work day, “Mulisamula” was characterized by main baraza gathering, “Ibalaasa-inene” where the Chief would meet with location leaders for updates on issues. This is today a Monday.

Following “Ibalaasa-inene” is “Ibalaasa-ike”, for second baraza gathering. The three days remaining for the week were for several activities including market days. This is illustrated in chart Ileseni 18mb.

From Ibalaasa-ike are “Mukavaga, Mukane & Mukataano” days. Sometimes either of them is regarded as “Mukiitu” for market day. However with the opening up of many markets in Logooli areas any day would be a market day somewhere. Traditional Market day in North Maragoli was on Thursday, “Mukane” at Mudete Market. It is still a main market day today and the calendar can mark “Mukane” as “Mukiitu”.

“Masiiza gane galoombaa umueli,” for four weeks make a month. The months, “mieli”, are twelve. They include; “Januari, Februari, Machi, Aprili, Mei, Juni, Julai, Agosti, Septemba, Oktoba, Novemba & Disemba” as in Chart Ileseni 18md.

The months in the order can also be read, “mueli gua kutaanga”, first month; “mueli gua kane”, fourth month; “mueli gua likomi”, tenth month and so on.

The traditional counting of the months was partly with the moon from events as “Imbula ia igudu”, first rain, “Lilima” cultivation or “Kihalaato”, drought.

A year is distributed into two halves due to the planting seasons. The first and main planting season is “igudu” or “mumuhiga”. The second that starts from Septemba is “Kiuvi”.

Due to the irregular weather pattern and new crops, it is difficult to attach events direct with Graegorian Calendar. The month of Aprili for instance was known as “Muliigala-vukuusi” to mean, “crops covering tcultivated land as they now grow tall and broaden.

With changed weather patterns, planting (Litaaga) can go as far as “Aprili”. And if rains come early, “Kiuvi” can start before Septemba. The reading of the farm seasons can therefore vary from farmer to farmer or location to location. However the chart at Ileseni 18mc illustrates for your understanding.

Exercise

- List the days of the week and months in your notebook

- With each day/month, note what mainly happens in your location.

...

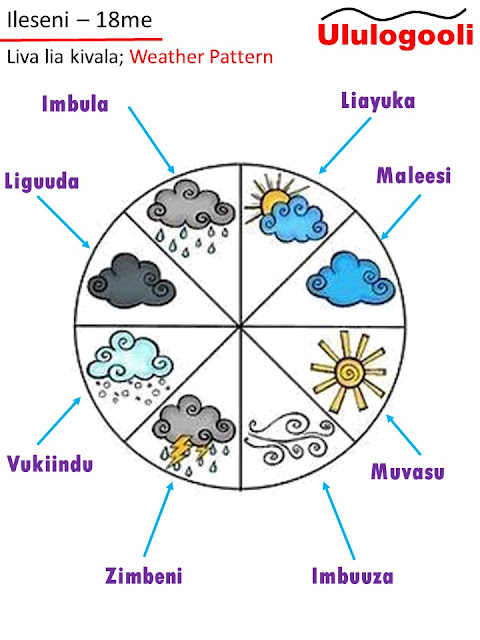

When it is sunny, it is "Kivasu", this can also be drought or dry season. The opposite is "muimbula", when there is rain and "mazi/vuzilili", wetness/cold.

Rain bearing clouds are "maleesi", "lileesi" for singular. Light clouds that sooner get lost in the skies are "liayuka" or "mayuka" for many.

The darkening of clouds to cause rain is "liguuda", while to rain is "kukuba". Rain is "imbula" and is sometimes followed by strong winds (ihuuza) or thunder and lightening (ikuba na luheni?).

Chart Ileseni 18me illustrates weather pattern.

...

Holidays and special days

During the year, there is the marking of special days as holidays (mahoonga) or rememberances (liizuliza). These days are mainly in English and Kiswahili as Valogooli do not have several special days, save for 26th December knows as "Maragoli Cultural Festival".

"Some argue that 26th December is "Vukulu"(Traditional) Day while others says "Menyakulu<menyangulu>" (As of old) Day.

For the rest of Kenyan Holidays or International markings, Ululogooli starts with "Lidiku lia..." for "Day of...". New Year, for instance is "Lidiku lia kuigula umuhiga" for "Day of opening the year".

With Kenya having Utamaduni Day (Culture Day) on Octobert 10th, it comes before the traditional Culture Day, 26th December. Cultural celebrations for Valogooli are then left for December.

The rest of the Holidays are as outlined in the in chart Ileseni mf.

...

Body Parts

The body parts of human body also make up the collection of Logooli nouns. Being conversant with the naming adds to the collection of vocabulary to use in writing. Charts Ileseni 18 to 18nj illustrate:

Notice the words as “itwi” in chart Ileseni 18ne. “Itwi” is “head”, here of a different size and performance as “Mutwi” of chart Ileseni 18n, The shared root word, [-twi] is head. Prefix “mu-“ is for neutral while “i-” is a look-like, a small head.

Other grammatical words are “Kiava”(not <chava>), “Iluhu”(not induhu), “Lugoma”(not <logoma>) and more as in the series charts Ileseni 18n to Ileseni 18nj.

Sides are divided into four; head side is “imutwi”, he back is “imugoongo”, the tail end is “mukila”. The right side is “-lungi” while the left is “-mosi”. Tjhhe right hand is “mukono-muluungi” while the left is “mukono-mumosi”.

Exercise

1. Draw the human body charts and label them at your notebook

2. Note the areas unnamed and inquire for the names

...

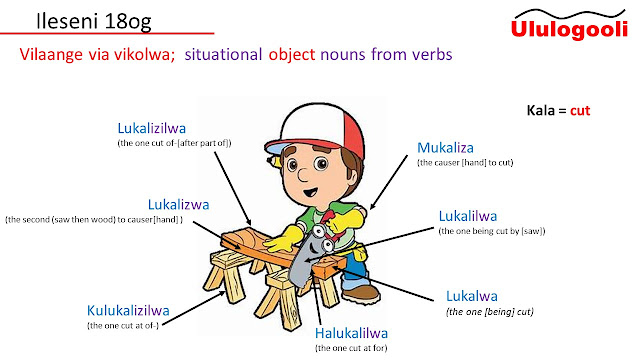

Nouns from Verbs

Lulogooli nouns are also derived from verbs. That from the “action/acts” of a person, a naming of the act or person is given.

For example, a teacher is “muigizi” from the verb, “igiza-teach”. A cook(cook=deeka) is “mudeeki”, an old man (saakula=grow old) is “musaakulu” and an old woman (keela=grow old) is “mukeele”.

It is important a learner had a look into the nature of the nouns arising from actions because of their different connotations, derived from structure.

In the given noun examples, they all happen to end differently; “muigiz.i”, “musaakul.u”, “mukeel.e”. This lesson attempts to introduce the learner to different noun constructs from verbs.

Borrowing from verbs structure, their three endings are, -a, -e and –i for immediate, past and future doing. Replication to nouns, it would mean nouns also have times of their naming!

By that, what is cooking if is “kideek.a”, what will be cooked if “kideek.e” then what has been/will have been cooked is “kideek.i”.

We have cases where nouns have endings “-o” and “-u” too. Nouns “muumbak.o” for building/construction and “Musaakul.u” for old man are from verbs “umbaka=build” and “saakula=get old” respectively.

With five noun endings, (-a, -e, -i, -o, -u), with the first three already categorized as “tense nouns” endings “-o” and “-u” would imply “resultant doer” and “object doer” respectively as at chart Ileseni 180c.

And as a rule, a noun is initiated into a part of speech by having a noun class reference. Chart Ileseni 18oc lists the noun classes from which a pick is enjoined to root verb and later an ending is input.

The ending can further be opened up to include verb inflections as “-w-”, “-ilw-”, “-z-” and others. These inflection, discussed at length at Lesson 20, mainly show relationship between an action and the receiver.

For an object noun from a verb, ending “-w-” refers to “done-to-it/victim”. If “Mudeek.a” is the cook, “Mudeekwa” is the cooked and so on. Chart Ileseni 180g illustrates better with “kala-cut” scenario.

Still an open area for further input, this lesson notes the various noun derivations from verbs and several endings, from where a writer or a speaker chooses in aim to communicate specifically.

Exercise

1. In your notebook, make notes by going through charts Ileseni 18o

2. For charts 180d and 180f, pick your own verbs and input, reading loud to internalize

...

Place names

A place name as “Nairobi” serves a little purpose in grammar. For a place in Lulogooli is either “directional, in, at, on or of” for “Inairobi, Munairobi, Hanairobi, Kunairobi or Kianairobi/Uanairobi” respectively.

Names of places are another set of nouns important for our consideration. Though in brief, this lesson introduces us to the different ways of place naming in Lulogooli.

A place name can be a result of a famous person (e.g Uaodanga<Wodanga>), a historical incident (e.g Kiavakali<chavakali>) or other reasons, some hardly known. This can be further studied in onomastics, a linguistical branch of names.

Place names, though in the bracket of proper nouns, are not as people names. With people names there are no prefixes. But with place names you are likely to have or interchange them.

We have place names as Ivusaali, Uaodanga, Hamuyundi, Kiamakaanga and Mungoma. They are prefixed “i-, ua-, ha-, kia- & mu-” respectively.

By interpretation, “i-” prefix is for a larger area, in the direction of. That is courtesy of compass directions. With that we also have place names as “Inandi, Ivo(imbo), Imuduungu, Isavatya” and more.

Prefix “ha-” takes a specific point from a larger area, perhaps the center. It also denotes a reduced area. Place names as “Hamuyundi” and “Hambale” are to mean ‘specific point’, therethere.

Prefix “kia-”, commonly <cha>, is mostly a characteristic feature of a place to its naming. “Kiavakali<Chavakali>” is named after women (vakali), “Kiamakaanga<Chamakanga” is named after makaanga, (guinea fowls).

Note that “kia” is a function of “kivala” (place). “Kiavala kia” is place of. So that Kiavakali and Kiamakaanga are known in full to be “Kivala kia vakali” and “kivala kia makaanga” respectively.

Prefix “ua-”, randomed “<wa/we/wi/wo/wu>” depending on the attached root name, is found for place names as “Uaodanga<Wodanga>, Uaengondo<Wengondo>, Uaonamu<Wonamu>” etc. Prefix “ua-” is possessive, the place known to be of the person or related in way.

Note also that “ua-” is a function of “luvega”, (side, place). “Luvega lua Odanga” (Side/Locality of Odanga) is further reduced to “Ua Odanga” and enjoined to beget “Uaodanga<Wodanga>”.

For “ku-” and “mu-”, external and internal areas respectively, are hardly prefixed as proper place names. Perhaps derived. “Kunairobi” is “on the outskirts of Nairobi” while “Munairobi” is “in the centre (CBD) of the town”.

Exercise

- Write down the places you know of.

- Using the mentioned place prefixes, classify your listed place names accordingly.

...

Clans of Logooli and reference to tribes/races

Clan names of Logooli are a key component of speech and also in writing. Knowing them is important as it adds to the collection of nouns.

The clan names help identify people with their ancestry. This is important in going about with traditional practices as marriage and other customary demands that only a clan member can do (or not do).

A common intoductory question is asking about one's clan; "Ivi ni muyaayi/mukaana ki?" Then the answer is always "Inzi ni muyaayi/mukaana Musuva", where "Musuva" is one of the clans of Logooli.

There are more than 60 clans in Logooli community. A brief history of them all is that only a few are said to be of direct lineage of Mulogooli, the tribe’s founder. See listing at chart Ileseni 18ra.

Some of the clans had already settled in what would become the ‘Maragoli region’ while others came with ‘Logooli Migration’. Others would later follow.

Ethnographer H.K Mwingisi asserts that the early clans and later ones would be absorbed to form a merged tribe, The Logooli. All may have be Pro-Bantu speakers. Settling of the two elder sons of Mulogooli (Saali and Kizungu) in East happened around AD 1900 when other clans were already living there. The clans would later be counted as part of the two.

Today the populations have increased, dispersed far and wide and what used to be a small clan is a tribe in comparison. Marriages within a clan are still disallowed, widening the incest definition in the enlarged clans.

A clan member is prefixed, “mu-” as in the case for “Musaniaga, Musaanga, Mudidi” while their plurals prefixed “Va-” as “Vasaniaga, Vasaanga, Vadidi” respectively.

The root clans names, “-Saniaga, -Saanga, -Didi”, are said to stand for ancestor’s name. In other cases they refer to an ancestral characteristic, example as “-Igina (for Vaigina)” said to have been found on a stone, “ligina”. Or “-Keveembe (for Vakeveembe) associated with thatch grass, “iveembe”.

Some clans have two names or can be referred to in more than one way. An example is “-Saniaga” that is also know na “-Kamnara”. Another is “-Gisunda” also known as “Vavai” in Tiriki.

Generally, from individuals to clans to tribes, those who belong to a different tribe are referred to by their larger community as in chart Ileseni 18rb. Sometimes a non-official colloquial name is used. A white person, “Musuungu”, can also be called “Mulaaya” to mean of “higher/soft standards”.

Excercise

- What is your paternal and maternal clans?

- What is the history of your paternal/maternal clan? You may ask your older clan mates and write down

Comments

Post a Comment